Using Data to Motivate the Post-Novice Lifter

Everyone can use a little extra motivation. So let's get creative with PRs.

Great products are based on insights about the people that use them. When I was at MapMyRun, we based our roadmap on three interconnected insights that are relevant to any fitness product:

- Everyone wants to get better. No matter where someone is in their fitness journey, everyone wants to improve. The common thread between trying to qualify for the Boston Marathon and training to finish a 5K is the desire for self-improvement.

- Everyone can use a little extra motivation. Getting better requires consistent training. And while some are more naturally motivated to train than others, even the most dedicated athletes need a little extra push now and then.

- Getting better is addictive. Once a person gets a taste of improvement, they get a craving for more. This craving fuels the motivation to train, and so on. Getting people into this virtuous cycle of training is the sweet spot for any fitness app.

Strength Training Novices are Easily Motivated

I've personally experienced this virtuous cycle of improvement but in the form of weightlifting instead of running. I discovered the Starting Strength Linear Progression, a strength training program for novices, as a form of rehab after back surgery. Weight training turns out to be an even better example of the "getting better is addictive" phenomenon because novice lifters can improve so rapidly and measurably.

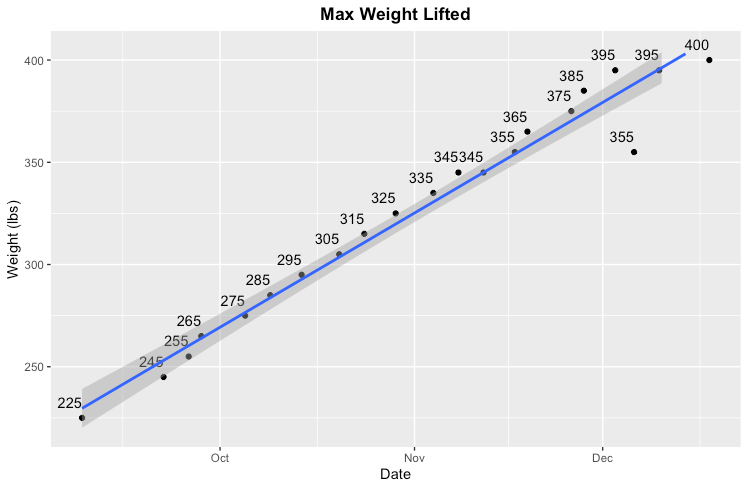

The Starting Strength Linear Progression involves four1 barbell exercises: the squat, the deadlift, bench press, and overhead press. The lifter rotates among these exercises, adding 5 pounds of weight to each lift every session until they run out of gas. It’s called linear progression because you can plot your lifts over time and they form a nice straight line—at least for the duration of your time as a novice. The graph below shows the linear progression of my deadlift in late 2017. Each column shows the heaviest weight I lifted in a session (usually for 5 reps, until I topped out at 395, which I could only lift twice).

Each point on the graph above can be thought of as the beginning and the end of a complete training cycle. This is the beauty of strength training for novices: You get rewarded with a PR in every session!

But all good things must come to an end. Eventually, a novice lifter won’t be able to make progress in every session, which according to Starting Strength's definition, means that they are no longer a novice. As an intermediate, training cycles will become longer and more complex, which can create a couple of problems for the lifter:

- The relationship between the inputs (training sessions) and outputs (strength) becomes less clear.

- Motivation may decrease because each workout is less rewarding.

Advanced PRs: Motivation for the Post-Novice

For now, I'd like to focus on the second problem—the problem of motivation. One obvious source of motivation is to provide the lifter a broader set of PRs and insights than a paper logbook can provide.

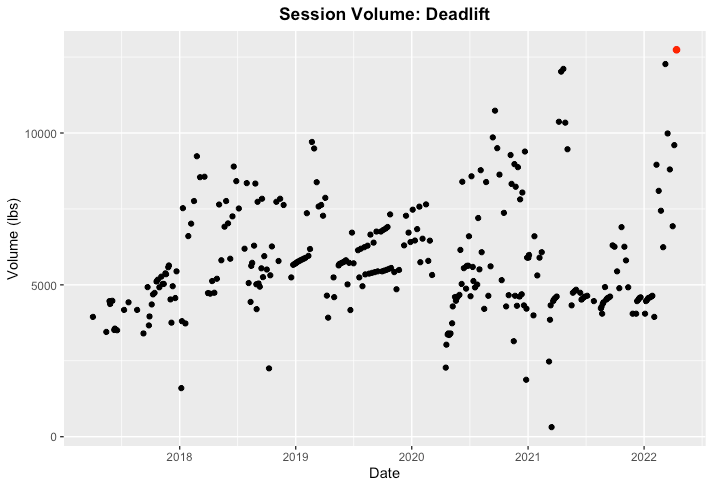

Let’s go back to my deadlift. It’s been over three years since I hit a true one-rep PR on the deadlift. But there other milestones (besides the 1RM) that could serve as a small reward after finishing my workout. For example, I recently had a particularly high-volume2 deadlift session and it made me wonder—could that have been my highest-volume session ever? I took a look at my data, and here’s what I found. The following chart shows this session’s volume in red.

Turns out it was my highest volume deadlift workout ever: a total of 12,740 lbs. lifted3. It may not be the type of PR you'll put on your Instagram profile, but understanding session volume is a nice little reward that could be provided to the post-novice.

We could also look at individual sets within each session to provide the lifter with a sense of progress. On another recent morning I deadlifted 405 lbs. for three reps. I knew this wasn't a "true PR," but I also knew that I hadn't lifted 405x3 in a quite a while. How long had it been? Looking back at my data, I found that it had been over two years! The following table shows the last five times that I lifted at least 405 for at least 3 reps.

Date Weight Reps

1 2020-02-22 410 3

2 2020-01-28 405 3

3 2020-01-18 415 3

4 2019-12-28 405 3

5 2019-06-13 410 3Clearly rep-PRs can be a motivational tool for post-novices, and we've now also seen that adding timeframe as a filter can help us get more out of these PRs.

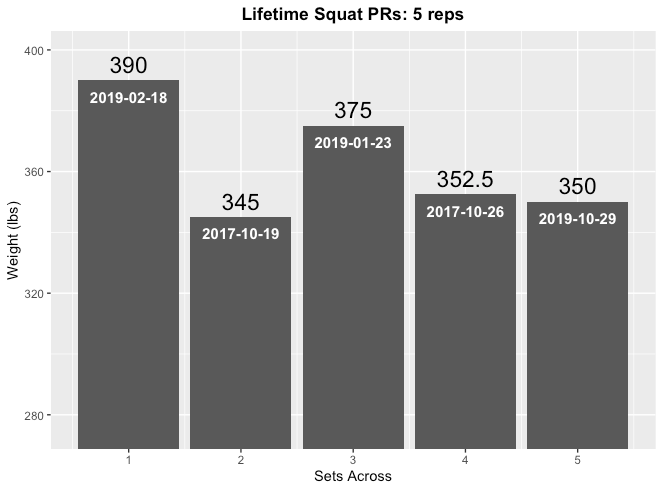

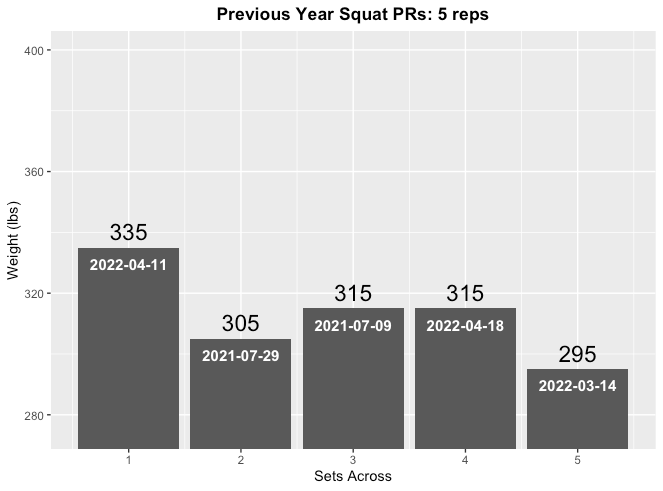

More advanced lifters might also want to keep track of PRs for "sets across." In the Starting Strength world, it's common to Squat, Bench, and Press across three sets of five reps. So let's take a look at squats for five reps. What's the most weight I've ever squatted for one set of five, two sets of five, and so on?

Unfortunately, all of these are from 2019 when I weighed a bit more, which puts them quite out of reach for now. Let's re-run that query for the last year. These values will be more motivating as something to beat.

Sadly, this year's numbers are pretty far behind. But this actually makes the case even more strongly: My lifetime PRs are 3-5 years old, making them irrelevant and certainly not motivating to me now.

Conclusion: The Value of Digital Tracking

It will probably be a while before I hit a true one-rep-max on the deadlift or squat again. Given that reality, it will be a great benefit to me as a lifter to get some of these additional insights as I continue to train. So far, we've identified three additional PR types, each of which can be filtered based on timeframe to yield dozens of specific PRs to track.

| PR | Timeframe |

| Total session volume for a particular lift | Lifetime, Last year, etc. |

| Rep-PRs for each lift across common rep ranges | Lifetime, Last year, etc. |

| Sets-and-Reps PRs for each lift | Lifetime, Last year, etc. |

As basic as these insights may seem, none of them would be possible if I hadn't tracked my lifting data digitally. However, most post-novice lifters track their training with a paper logbook—and many coaches are adamant that these physical logbooks are the best way to track. I would suggest that there are two major problems with logbooks. First, a paper logbook is too easily lost. I actually don't have access to my very early lifting data because my logbook disappeared from my gym. But the second and more important problem with paper tracking is that even if you have the data, it is mostly trapped in the notebook, leaving many potential insights hidden.

Staying motivated is relatively easy for a novice. You get stronger every session and the numbers go in only one direction: Up. But the longer you lift, the more it pays to get creative with PRs. Because no matter how strong you get, everyone can use a little extra motivation.

Notes

- Strictly speaking, LP involves a fifth exercise: the power clean. But for an older and "less athletic" lifter like me, coaches often leave this exercise out. More discussion on that here.

- Volume is simply the total amount of weight moved for a given exercise. In other words,

<volume> = <weight> * <reps> * <sets>. - This number includes all of my warmup sets, which some would suggest excluding from volume calculations.