What Calendly Reveals About Our Nature

A digression into one of my favorite topics: how we use language to play an invisible game of status

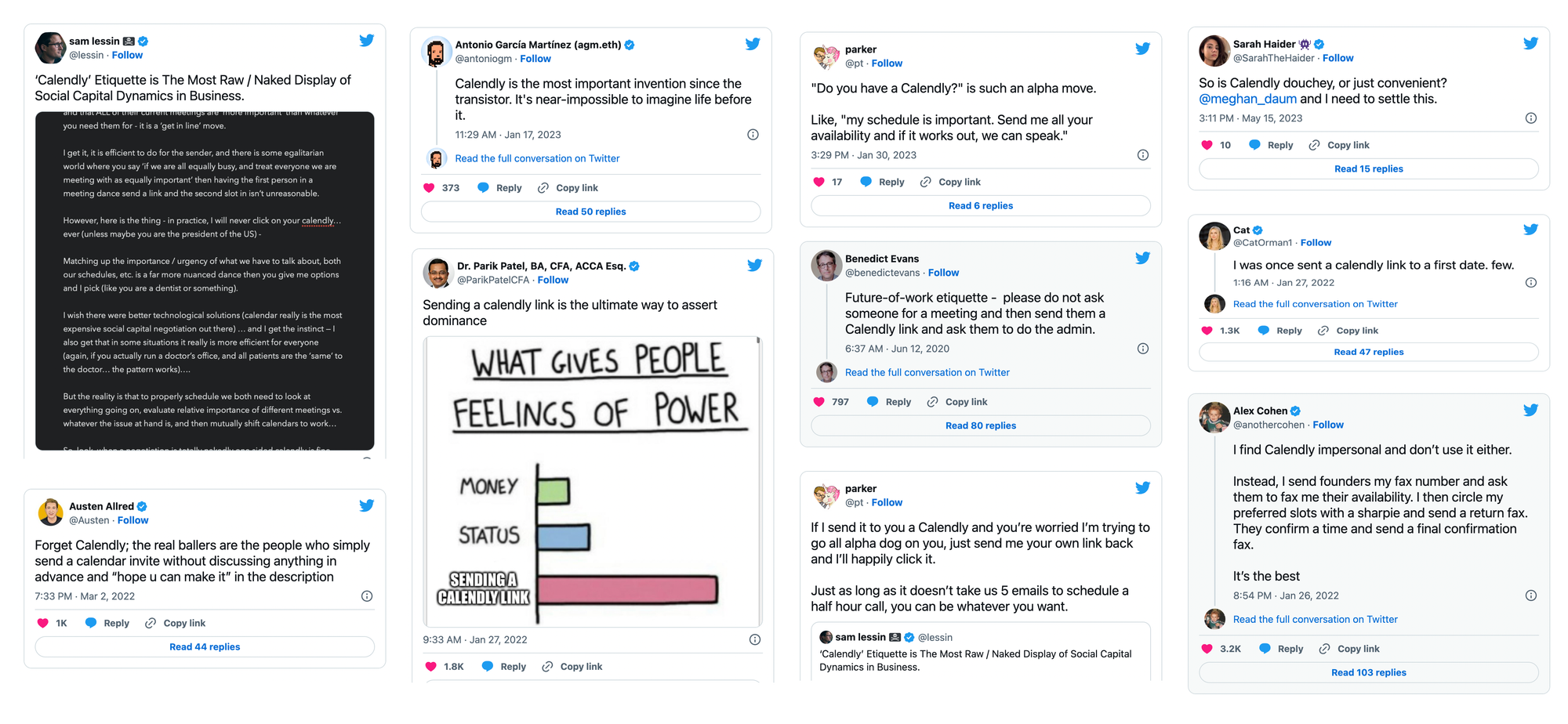

Calendly is a scheduling app that is very convenient but a little rude. Just how convenient? And how rude? People are divided. Why does a scheduling app provoke such strong feelings? The answer involves a digression into one of my favorite topics: how we use language to play an invisible game of status (whether we realize it or not).

The Case For Calendly

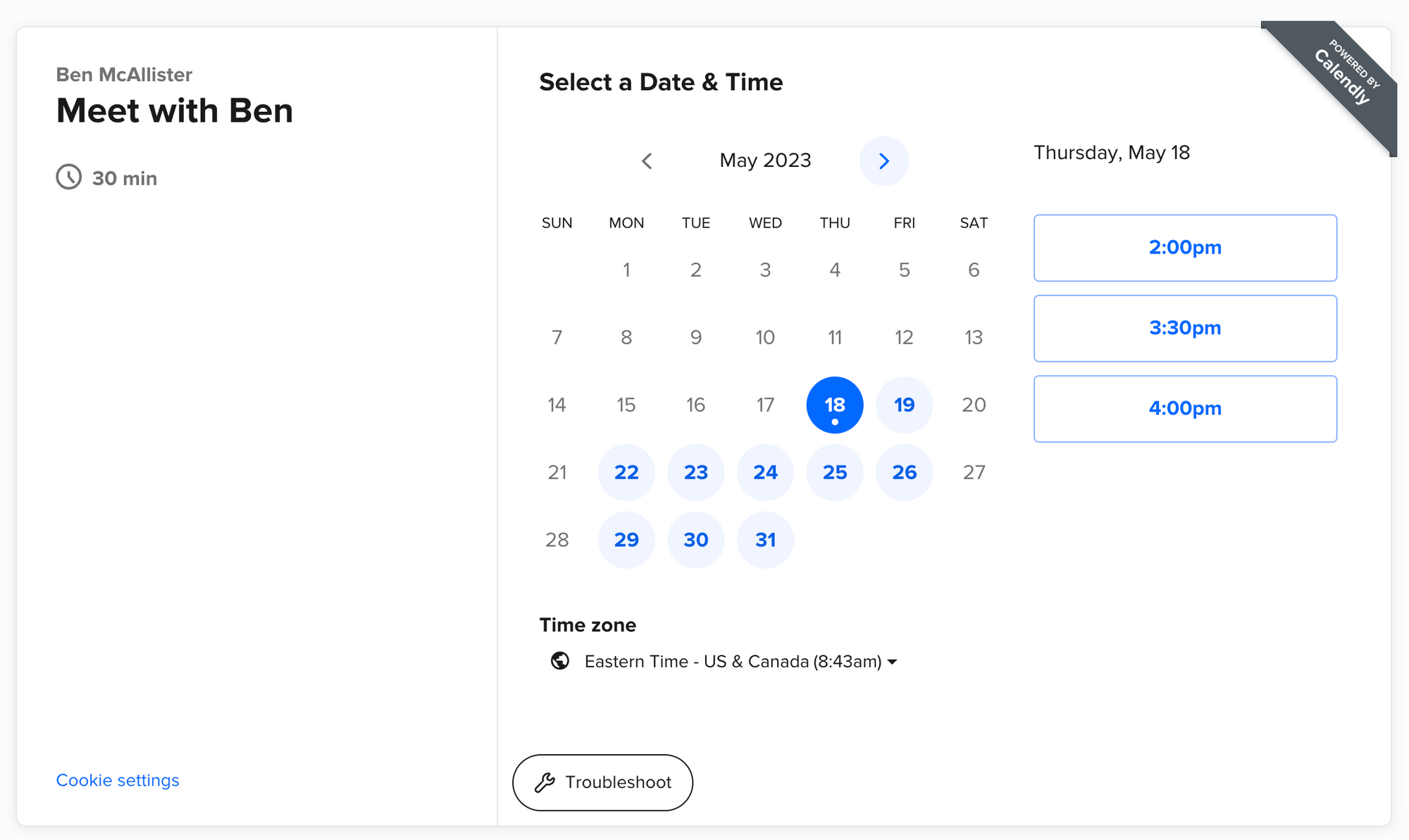

Everyone hates email. And because scheduling meetings can require a lot of emails, people really hate scheduling meetings. All that emailing feels like wasted time. Calendly offers a way to skip the email and just book the meeting. Just send a link and let your guest pick any available time.

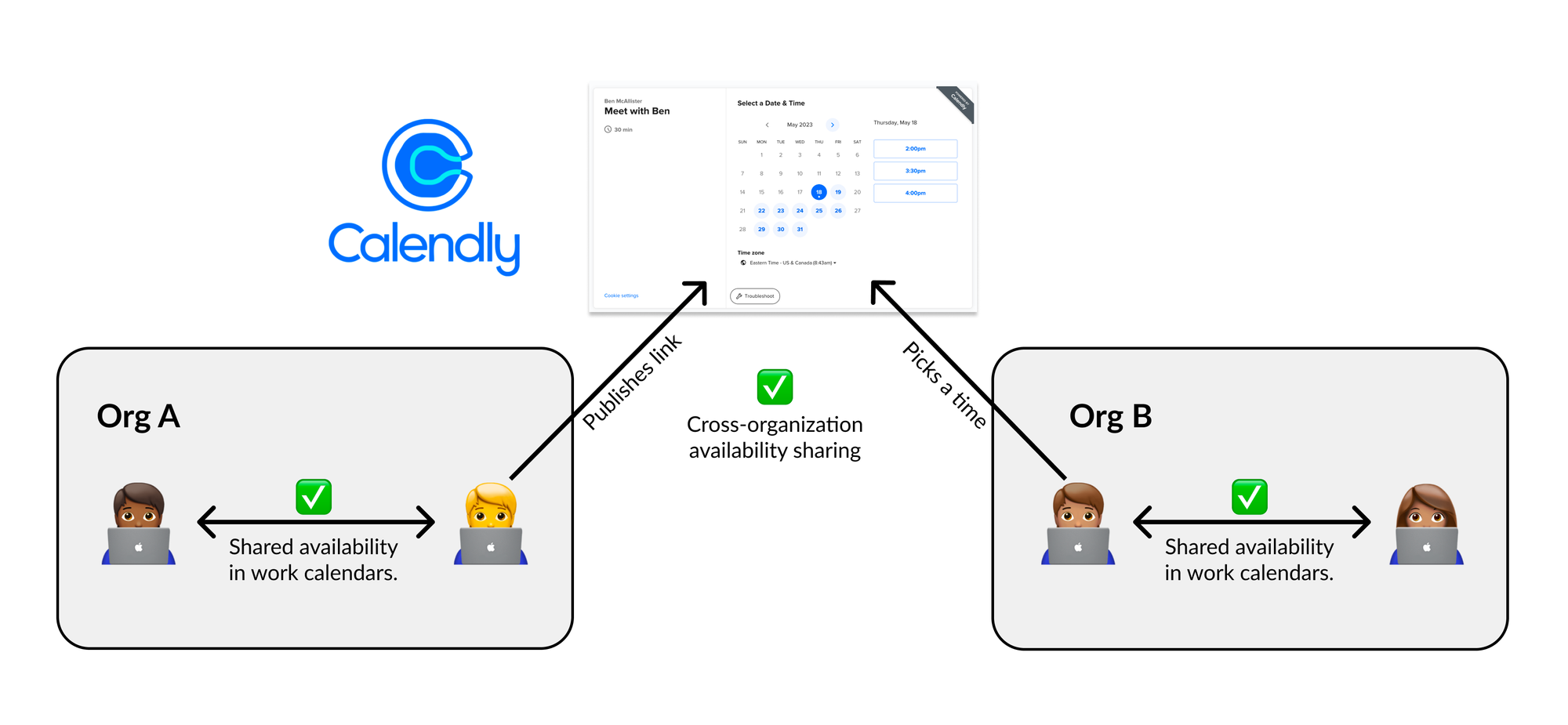

Sharing availability for meetings is not new. But before Calendly, this feature was available only to people within the same organization and calendar system. Calendly's innovation was to make availability visible across organizational boundaries.

The end result is a more direct path to a meeting. But this directness is also what provokes such strong feelings about Calendly.

The Case Against

Humans don't communicate like computers—simply passing bits of information back and forth. As Aristotle said, we are political animals. Our communication always has a social dimension. Consider the different ways of asking for a meeting, depending on whom one is addressing:

- If I ask my boss for a meeting, I use deferential language to signal my awareness of their high status: I hate to bother you with this, but...

- When talking to a peer I've worked with for years, I use informal language to signal friendship: Yo...

- If I ask to meet with someone new from another department, I might use transactional language to indicate a mutual exchange of value: I'd love to discuss how the product team can better support you.

Calendly may save coordination time, but it also strips away our ability to navigate the subtleties of our relationships.

Relationship Structures

The above three examples are not chosen at random. Each represents a major relationship structure identified by the anthropologist Alan Fiske. According to Fiske, these relationship types are like a system of grammar—something that we all use effortlessly, even if we're unaware of the exact rules. He actually identifies four distinct relationship types:

- Authority Ranking: Relationships of dominance characterized by differing levels of authority, prestige, or privilege.

- Communal Sharing: Family-like relationships of equals characterized by resource sharing and a sense of unity.

- Equality Matching: Non-intimate relationships characterized by reciprocity.

- Market Pricing: Relationships characterized by economic exchange involving pricing.

Each of these relationship structures has its own set of unwritten rules. When we openly break these rules, life gets awkward—or worse. Imagine leaving a dinner party with friends (communal sharing) and attempting to thank them with cash (market pricing). Folk wisdom also warns against mixing relationship types: Don't go into business (market pricing) with friends (communal sharing). Don't "keep score" (equality matching) in a marriage (communal sharing).

But life isn't so simple. Few of our relationships belong exclusively to a single category, and we change modes effortlessly. So why do some "mode changes" result in outrage or hurt feelings while others go unnoticed?

Using Language To Navigate Relationships

In The Stuff of Thought, Steven Pinker argues that we use language to strategically reinforce or move between relationship structures. "We choose our words carefully," he writes, "because they accomplish two tasks at once: convey our intentions, and maintain or renegotiate our ties with our fellows."

So, when we need something from a superior, we use deferential language. ("I hate to bother you with this, but...") The content says, "I need you to do something," but in a style that says, "I haven't forgotten you're the boss."

Sometimes, instead of reinforcing one type of relationship, we aim to subtly navigate to a different one. For example, the boss might use the language of communal sharing when acting as a superior. "It would be great if you could take notes during this meeting" is a hierarchical order but couched in the lingo of communal sharing, which might serve to make a meeting feel more collaborative.

Games We (Must) Play

Scheduling a meeting isn't a simple transaction. Scheduling is a status game, which means that The First Fundamental Law of Status Games applies: You can't opt out. In his book The Status Game, Will Storr writes:

We play for status, if only subtly, with every social interaction, every contribution we make to work, love or family life and every internet post. We play with how we dress, how we speak and what we believe... It’s a game that never ends... There’s no opting out of the game. It’s written into our brain and the brains of everyone we’ll ever meet.

Status games can feel like a waste of time and energy. So the idea that we can just skip over them can be tantalizing. "If only we could skip the niceties and get down to the heart of the matter," we tell ourselves! I've certainly made this mistake more times than I'd like to admit.

Calendly is not a way to skip the game, but an attempt to rewrite the rules of the game. Certain types of meetings like scheduling a product demo with a sales team are a natural fit for these rules. But when the stakes are higher, or the relationship is unclear, it might be wise to ask yourself: whose rules should I be playing by?